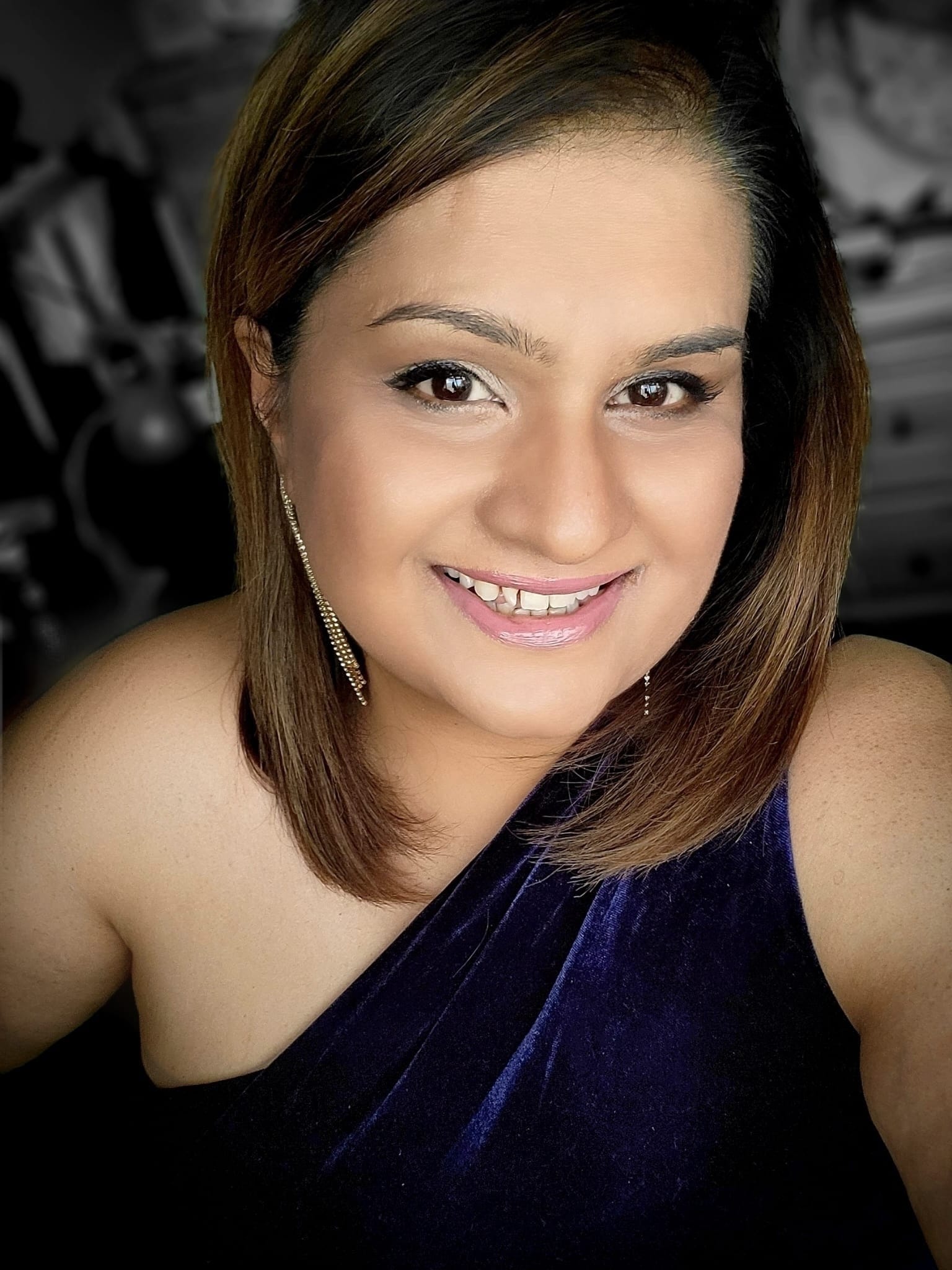

My challenges in life began as a young child, growing up in an abusive family home in the UK. I had been removed from my native Sri Lanka at age 5 when my mother decided to migrate with me to the UK. I was traumatised by the sudden change in my daily life; no more loving external family around me, only my distant and aloof mother and a violent and abusive stepfather in a new, very cold country. It was a shock, and there would be many more, but this experience, I think, really shaped my understanding of the concept of terror, human security and the experience of vulnerability and injustice.

I learned to find refuge in books and storytelling and made some good friends, and those two aspects would become hugely influential in my life later on — my love for the written word and knowing how to look for good people, diamonds among the rough. No matter how dark life gets, those people are there, keep looking.

At the time that these challenging experiences occur, especially as a child, it's difficult to process and analyse, but later, as an adult, looking back reflectively, I learned a lot through my own journey. Migration has a deep effect on people; it can be traumatic and for some it can be hugely beneficial, but it's always important to consider migration as an important part of someone's identity.

Though there was a long winding road ahead for me — including being taken into care, and learning about family life through my foster family, who stabilised my life — I found my way back to the books and academia, back to processing the challenges I first experienced, and against all odds, I found my way to giving a good family life to my children.

My PhD was about migration, human security and the path to terror for women in the UK, and it's easy now to look back and see how I ended up at that destination. However, getting there was not easy; teachers told me I would never go to university, that I wasn't intelligent enough. I believed every word, and it was my belief in them that held me back. I didn't have the motivation to go to university till my 30s. I have learnt to believe in myself and not be reliant on others' opinions of what I can achieve, who I am, and what lies in my future.

During my research years, I came across thousands of British women who had migrated and become survivors of extremism in the home and were subjected to a personalised form of poverty (whereby they were singled out for a life of hardship while others were glorified and rewarded).

This is the story of many female migrants in the UK. Some were married as children, some were passed around families as sex slaves, and others were violently beaten and enslaved after marriage. They are not in small numbers. In one survey I did among 1500 south asian women in a single location, 95% reported sexual violence. We certainly live among an architecture of gendered violence that is hidden in plain sight. It became my life's work to throw light upon that world and to bring those women’s life stories to the attention of the government.

However, my work has not been all about women as victims; it has also been about women as perpetrators, in particular, female suicide bombing in the UK. Due to the mainstreamed misogyny in the UK and the patriarchal ideas of women only as nurturers, not as vulnerable to political radicalisation, the security services were all at sea with that subject. It was a real wake-up call, and today things are very different, with a more nuanced understanding of women and terror. A number of mass casualty incidents have been disrupted or prevented due to these changes in critical thinking and practice.

Disrupting the ways of thinking in national security and the acceptance of women as political actors with agency took a long time. It was only 2013 when Britain started putting women in combat roles in the army, whilst in my country of birth, Sri Lanka, they had been doing it for decades. Britain has never really led the way in equal agency, and this is apparent in these areas even today.

During a counter terrorism command unit training day, I once asked the attendees to put their laptops down and for men to go to one side and women to the other. There were around 200 men on one side and 7 women on the other. I started the session by saying, “I’m here today to talk about women and terrorism, and there are only 7 people in the room who have done the reading”. Recruitment of women into the police forces was around 27% and into counter-terrorism, it was fractional. It was absurd, and for at least that day, it was obvious.

I have worked around the world lecturing and training in my PhD area and in the area of working collaboratively between major public agencies and communities. Whether in the Middle East, the West or South Asia, I always encourage girls and women to get an education in an area where they have a passion. The reason for this emphasis is that education gives you the tools to articulate your thoughts into a workable action plan for others, even for the nation. It provides a foundation on which to stand your ground and a platform to lead.

For me, it was not an interest; it was a mission. Violence and terror were normalised. It may seem dramatic, but it’s just one of a million harsh realities for thousands of British women and children. Likewise, the ‘kindnesses’ of my teachers' opinions were also harmful and reductionist. I wasn’t blinded by those false kindnesses as an adult woman. I had learned not to bow down to the prevailing wisdom but to question it. Education does that for you; a good degree will always teach you to question, and victimhood sometimes gives you the fire inside to go forward.

As a child, I yearned for my family in Sri Lanka, and over time, I returned regularly, sometimes for work as a security advisor and sometimes in disaster management. I reconnected with the family I had missed growing up with, and for a while, on a long contract, I enrolled the children in school there for a short time, which they loved. I am proud that my children grew to know the birth country of their mother and their extended family.

As a survivor, your heart is bigger, your soul is deeper, your understanding greater, and thus, your potential to disrupt...

Years later, I completed building my family home in Sri Lanka, as what we had when I was a child was destroyed during wartime. That was the realisation of a dream I had from those dark days in the UK, far away, a helpless child, yearning for adulthood when I would be in control of my life and back to safety among my family in Sri Lanka. I am also proud every day that I have contributed to the safety and public protection of both countries I call home. And in peacetime, wherever I am, I am grateful that I have survived and overcome the painful journey that got me there.

As a survivor, your heart is bigger, your soul is deeper, your understanding greater, and thus, your potential to disrupt the biggest threat to safety for women, silence, is thundering behind you, waiting for you to unleash it. So am I a Disruptor? Yes, every waking moment, and it has served me well.

Dr Michelle Brooks is an academic who works in gender and security, focusing on the intersection of domestic violence, gender, and national security. She has trained Police counter-terrorism command units in the UK, Europol, and CEPOL, and worked as a military instructor in the UAE, UK, and Sri Lanka.

Michelle also runs an NGO in Sri Lanka, which works on poverty alleviation and livelihoods transformation in hard-to-reach communities.

Michelle has worked in the House of Lords, Downing Street, the Home Office, and more than 50 NGOs in the UK to broaden participation and engagement between communities and the State. She has also conducted research for the government on the misuse of drugs like Khat and strategies to safeguard communities. Born in Sri Lanka, Michelle has lived in the UK for over 40 years with her husband and two sons.

Member discussion