I have always known I was adopted, and for as long as I can remember, I knew I was mixed race. My adoptive parents were very conscious – especially given this was in the 70s – that adopting a black child might be too much of a struggle in our predominantly white area. They thought it would be easier to adopt a mixed-race baby. They had suffered several miscarriages and wanted to give their love to a baby who had less chance of being chosen.

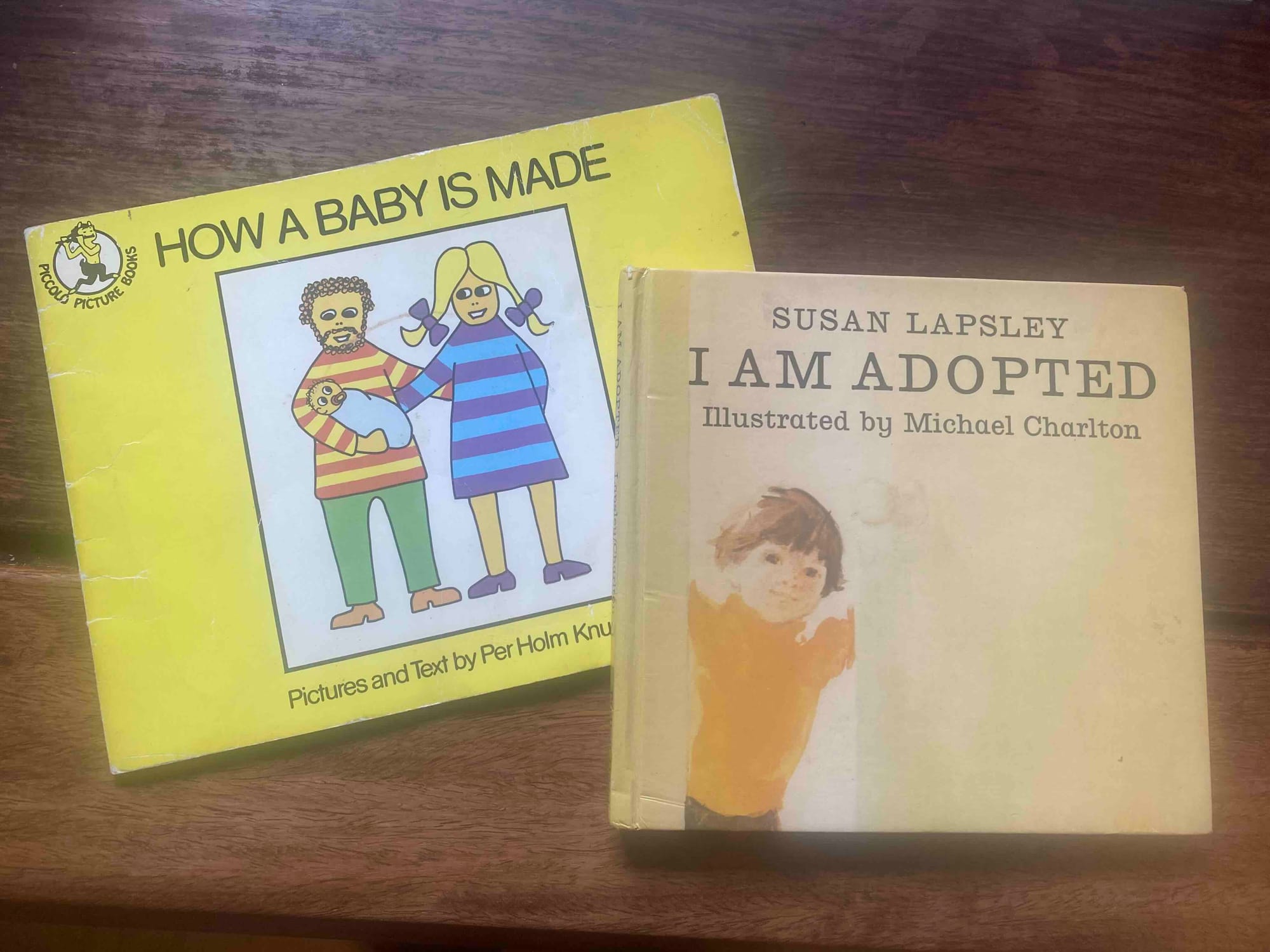

I remember from about age three having two books side by side: “How Babies Are Made” and “I Am Adopted.” After reading these, we read a letter from the hospital where I was born, which included information about my birth parents. It said my mother was 15 when she became pregnant, half Italian and half Sudanese, and living in the Ivory Coast. My father, also from the Ivory Coast, was half Chadian and half French (which I later learned was actually Congolese and Belgian).

So, I always knew I was adopted, always knew I was mixed race – half African, half European – and as I grew up, I looked different to everyone in my family, so it was also hard to hide!

My family made sure my difference was not seen as a problem - it’s funny, though, how when your difference is constantly pointed out, you never quite feel as if you fit in.

I grew up in a very loving adopted family with my English father, Canadian mother, an older sister who is six years older (their biological child), and a brother who is sixteen years older (from my father’s previous marriage). My family was full of love, encouragement and a real sense of openness and inclusivity. My brother and sister loved having a new baby to look after and the fact that I was mixed race and adopted brought an extra air of intrigue and interest.

My father would tell anyone who would listen about my ethnic background and was very proud. We were a Christian family, and church would play an important part every Sunday where my dad was an elder. Holidays were often in Canada with my mom’s family. We were a privileged family, my father ran his own business and worked hard. This work ethic was instilled in me from a young age and afforded us a very fortunate home life.

I have memories of being told, “You’re wanted” and “You’re special.” My family made sure my difference was not seen as a problem - it’s funny, though, how when your difference is constantly pointed out, you never quite feel as if you fit in. As a family, they went out of their way to support me.

Growing up, my ethnicity was recognised. I distinctly remember disliking the Barbie and Cindy dolls, so my parents took me to London where I could choose my own. I picked out an “Amanda Jane,” a short little doll with brown skin and dark brown wavy hair. I loved her!

I was occasionally racially bullied at school and remember coming home crying. Whilst my parents had not experienced racial bullying themselves and did not really know how best to comfort me, they certainly tried, giving me lots of love and telling me to be strong. In a predominantly white school in a predominantly white area with white parents, we were in unchartered territory. It was confusing to be taunted with “golliwog,” looking as light-skinned as I did, but it showed how my difference was seen by others, which made it hard to feel as if I fit in.

Being mixed race is incredibly conflicting. You don’t fit into either camp; you’re not black enough to be black, not white enough to be white, and it’s how others perceive you that really leaves a mark.

We talk about gaslighting today – the feeling that what you think you feel isn’t true. That’s how it felt for me. I would try to explain to my family what it felt like to be different, but they could never quite understand. If they loved me and didn’t care about my background, surely that made it all go away. They were proud to refer to me as exotic and, despite my different blood, they loved me. But this didn’t match with the taunts I received and how others perceived me, which in turn affected how I saw myself. Ultimately, I felt different, othered, which felt like a negative. I say this looking back, but I am in a very different place now.

My life changed somewhat abruptly as my adopted mother got cancer and subsequently died when I was 10. Understandably everything changed and being mixed race was one of many things I now had to contend with.

Being mixed race is incredibly conflicting. You don’t fit into either camp; you’re not black enough to be black, not white enough to be white, and it’s how others perceive you that really leaves a mark.

Filling out forms that don’t recognise mixed-race ethnicity has been a frustrating experience for me and still is. I have only ever been labelled as “other.” A few years ago, during a hospital check-up at the age of 45, I was finally able to tick a box that didn’t read “other.” I cried. “Other” implies that you aren’t part of us, that you haven’t been considered, that you don’t matter. Times are changing, and forms are improving as people become more considerate. All I can say is that it’s about time!

As I came into my teenage years, I felt very unattractive and ugly. My hair was a mass of unkempt curls desperately trying to grow out from a horrific cut (sheering) and I had no idea how to look after them. Neither did anyone else. I tried black salons and white salons, but neither understood my hair. My body felt wrong, I was too strong, big-boned (in my eyes fat) – certainly not the petite English rose type of body ideal that I aspired to and that my sister was blessed with.

When you’re young you just want to fit in, but I was never afforded that. It was very isolating. Being adopted into a white family, in a white suburb made it even harder. I had no one whose eyes were like mine, whose skin tanned the same way, or whose curls never went straight. No one around me was the same, and I couldn’t see myself reflected.

Whilst I looked different, I had no awareness of my cultural heritage or ancestry. I became fascinated by Egypt, as the paperwork left by the hospital alluded to part of my mother’s family originating there. I wanted to learn French, Italian, and Arabic, knowing they were the languages my birth mother spoke. Being mixed had a huge impact on my sense of identity and belonging. To the extent that, after graduating, I took a job teaching in Tanzania just to get to the African continent, even though it was nowhere near Sudan or Chad.

Frequently, even though I am stronger in myself now, I can still feel a lack of identity. It is a recurring emotion, but I also appreciate how silly it is. I even question whether I can braid my hair when it needs protecting as if I shouldn’t be able to do what my hair and I need because somehow, it’s not appropriate. Living in England has its challenges. For a very progressive society, racism runs deep. We are such a diverse nation, yet you can’t be English unless you’re genetically Anglo-Saxon and ultimately white; otherwise, you’re British. So, I have never been English, but I am British, only due to my adoption. That’s an identity conundrum right there.

We’re still living in a polarised world, where society will champion one group over another. But in my humble opinion, I don’t think it serves to give airtime to finding more ways to pitch minoritized groups against each other – we’re all struggling and trying to find a better way. Everyone has a unique story, journey and experience which will shape their perspective. Some will have experienced more struggles whilst others have greater privilege, but they all deserve a voice, and we need to understand this breadth of diversity in all its beautiful forms. We can’t criticise any one group for wanting to have their voices heard either, particularly when they’ve been denied it for so long; but that doesn’t mean we can’t share the baton so that everyone can add their contribution. Being mixed race could be seen to have its advantages, but discrimination and lack of representation are still that, no matter who is on the receiving end. As minoritized groups, we are stronger together, and together, we can make significant changes.

Understanding your own identity can be a struggle, and that’s okay. Find your inner strength and be kind to yourself; we’re all on a journey to be our best selves.

Today, being mixed race is becoming my superpower; it’s a strength and it’s who I am! I’ve had the privilege of straddling worlds, cultures, and identities, and none of them feels alien. Somehow, even when they’re not part of my makeup, I feel I can absorb, learn, and feel at home. When I travel, I’m never fully a local, but never fully a tourist either. Maybe I’ve become comfortable with being an outsider. Of course, I still have self-doubt and feel I am not enough, but this spurs me on to do better and be better.

I can’t change my ethnic makeup, nor do I want to. It’s why I started my business. I want us all to have access to be our best selves, no matter how we look. I have felt diminished in the past, being neither/nor, but I now have the confidence to own my space and have a sense of who I am. Perhaps not every day, but I am getting there.

I hope my story helped highlight something important: firstly, being mixed race is not only reserved for those half black and half white; we come in all varieties, which is beautiful, and our identities are not always as visible as you’d expect. And secondly, understanding your own identity can be a struggle, and that’s okay. Find your inner strength and be kind to yourself; we’re all on a journey to be our best selves.

Member discussion